ACSESSED: Cross-tenant network bypass in Azure Cognitive Search

TL;DR

This blog post provides a technical description of a 0-day vulnerability that I found in Microsoft Azure back in February 2022.

The vulnerability, which I dubbed “ACSESSED”, consisted of a cross-tenant network bypass, allowing anyone with the right amount of information to access data located in private instances of Azure Cognitive Search (ACS) from any tenant and location.

The vulnerability was reported on February 23rd and fixed by Microsoft on August 31st 2022. This blog post covers the following:

- How the ACSESSED vulnerability was first detected

- How it could be exploited

- The impact of the vulnerability

- Its disclosure timeline

- A high-level description of how Microsoft fixed the issue

Introduction

Over the past two years, Microsoft Azure has been confronted with a significant number of serious vulnerabilities such as Azureescape, OMIGOD, or the infamous cross-tenant bypass in the Synapse Analytics service to name a few.

Due to popularity of the Azure platform in the Nordics, our penetration-testing teams are often exposed to Azure environments of different kinds, complexities and sizes, making it easier to keep up with the fast-growing pace of new features released by Microsoft.

One day, a new feature suddenly appeared in the networking options of the ACS service, while conducting a customer engagement:

Based on the information provided in the portal, it seemed like the feature was supposed to create an exception in the resource’s firewall, so that accessing its data plane via the Azure portal was possible even when strict network restrictions were applied to the resource (e.g. exposed on a restricted public endpoint, a private endpoint or without any explicit network exposure).

Immediately, I started wondering how the feature actually worked under the hood:

- What are the actual IP addresses whitelisted in the firewall when enabling this feature?

- How does the Azure portal actually use these IP addresses?

- What does “Allow access from Portal” actually mean? Is this my instance of the portal, or does it make an exception for everybody?

As this was completely undocumented when I first noticed the feature back in February 2022, I decided to investigate it, to try understanding the consequences of enabling that new button.

Background

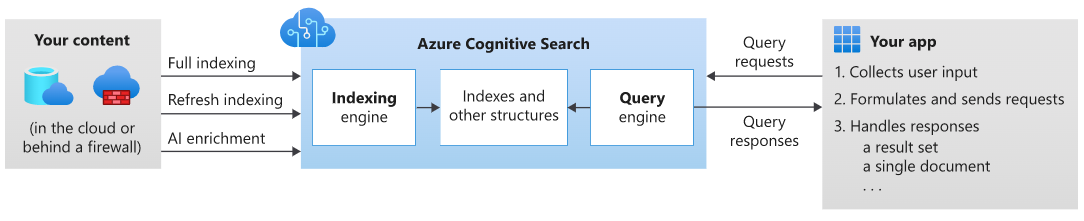

Azure Cognitive Search (ACS) is a very popular search engine service for full-text search, which essentially allows customers to search within their data in a very fast way using indexes. The service supports multiple types of search approaches, such as text search, fuzzy search, autocomplete, or even location-based search.

Figure 1: High-level architecture of Azure Cognitive Search – Source: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/search/search-what-is-azure-search

Detecting the vulnerability

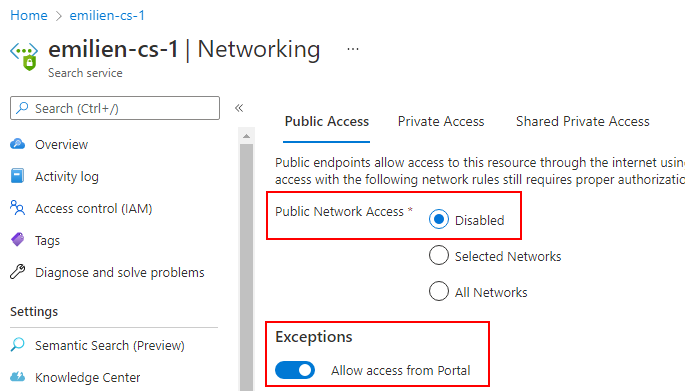

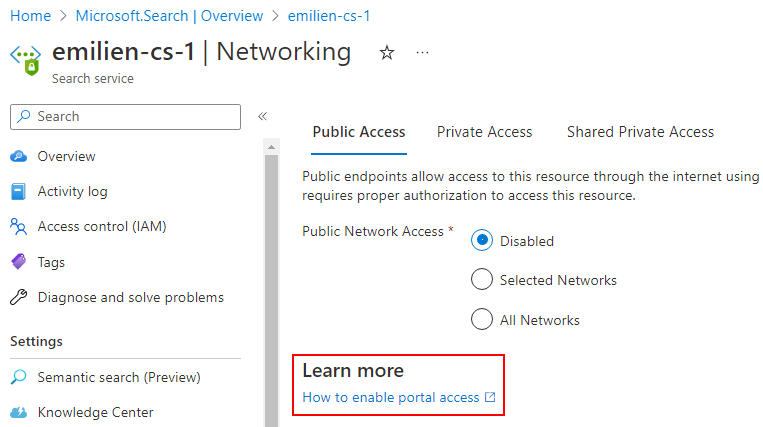

In order to investigate the new networking feature of ACS, I first started by deploying a brand new instance of the service in a test environment, using all the default options. I also made sure the instance was not exposed on any network, by disabling both public and private network access completely. The only networking option enabled at this point was the new “Allow access from Portal” configuration:

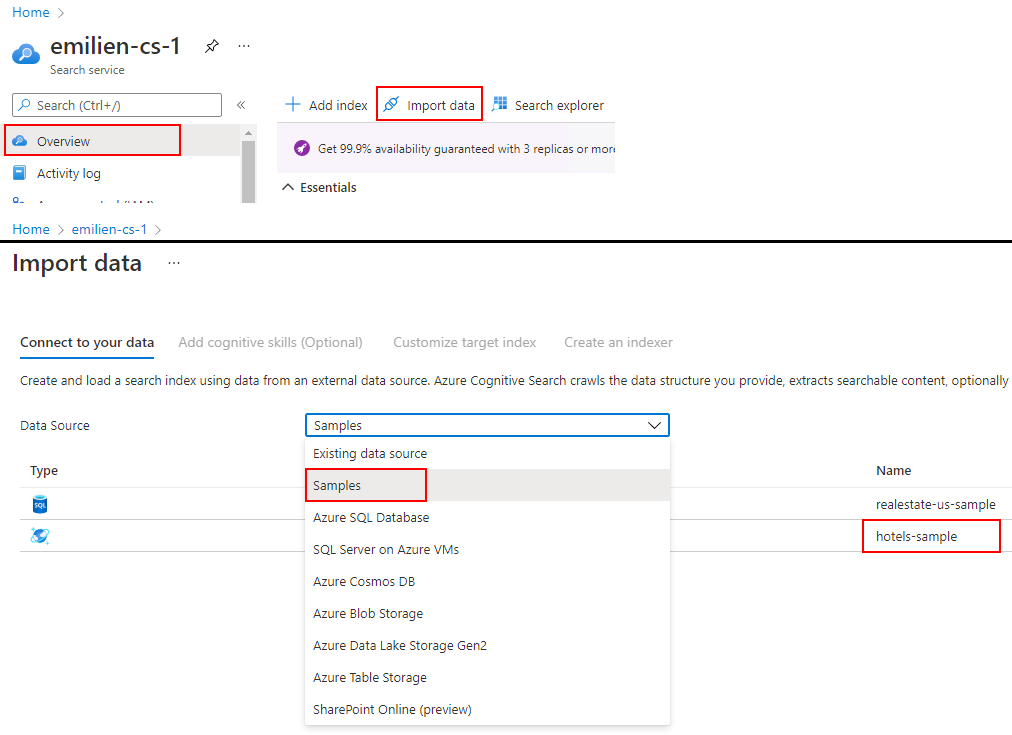

Additionally, I imported test data to the instance, using the built-in data source called “hotels-sample”, to have some data ready to query:

Once confirming that I could retrieve data from my network-isolated ACS instance via the Azure portal’s built-in search explorer, I started investigating the service to understand how that was possible.

First, I started looking at the instance’s raw configuration, as I was wondering what kind of IP address the new feature whitelisted in the resource’s firewall. To my surprise, no IP was whitelisted. Instead, the instance’s networkRuleSet.bypass property was set to AzurePortal, as follows:

According to the official documentation for the Cognitive Search API, the bypass property allows the specified origin to bypass all networking rules defined in the resource’s networkRuleSet.ipRules configuration (i.e. its firewall). In other words, that property was the one making it possible to reach the data plane of the ACS resource from the Azure portal, regardless of the networking rules defined for the instance. Note that only None and AzurePortal were valid values for the bypass property and submitting arbitrary IP addresses or strings was therefore disallowed.

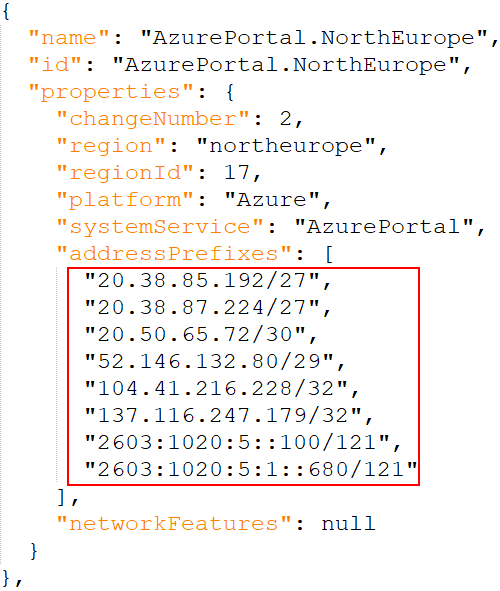

The AzurePortal value looked like a service tag, so I started wondering what kind of IP addresses might be whitelisted behind the scene. Based on Microsoft’s overview of Azure IP Ranges and Service Tags, it seemed like the effective IP addresses associated with the service tag varied based on global regions, which in the case of my ACS instance corresponded to the IP addresses of the North-Europe region:

At this point, I started to wonder if the “Allow access from Portal” feature simply allowed using the IP addresses associated with the AzurePortal service tag. At the same time, I felt like being able to impersonate IP addresses belonging to a service tag could potentially create huge security issues for other services.

The second step of my investigation therefore consisted of analysing the traffic sent by my client when using search explorer to retrieve data from the ACS instance. I quickly noticed requests towards the stamp2.ext.search.windows.net host, which according to Microsoft’s documentation, consists of the domain of the traffic manager and represents the IP address of the Azure portal in the current location.

At the time of the investigation, the IP address of the Azure portal in my region (North Europe) was 20.50.216.43. However, that address was neither contained in the IP range of the AzurePortal service tag for the North Europe region, nor was it contained in the IP ranges of other regions. I started to get confused at this point, as it was not clear what the AzurePortal service tag was really whitelisting behind the scene and what role the stamp2.ext.search.windows.net host actually played to allow retrieving data via the Azure portal.

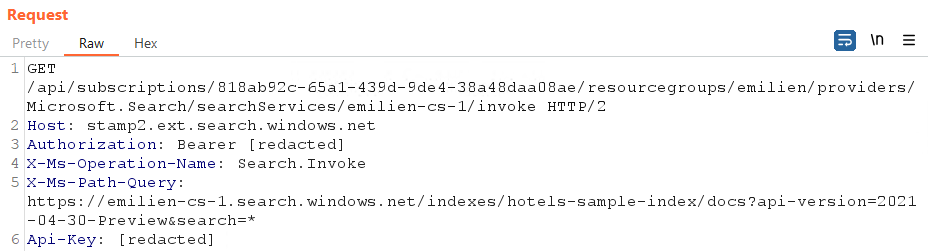

I kept investigating the requests towards the stamp2.ext.search.windows.net host and quickly noticed they were all hitting the same endpoint with the same set of uncommon headers:

As illustrated above, the requests were all hitting the /api/<path-to-resource>/invoke endpoint, and submitted search queries to the data plane of my ACS instance via an X-Ms-Path-Query header. Additionally, an access token was required for authentication, besides the API key of the ACS instance.

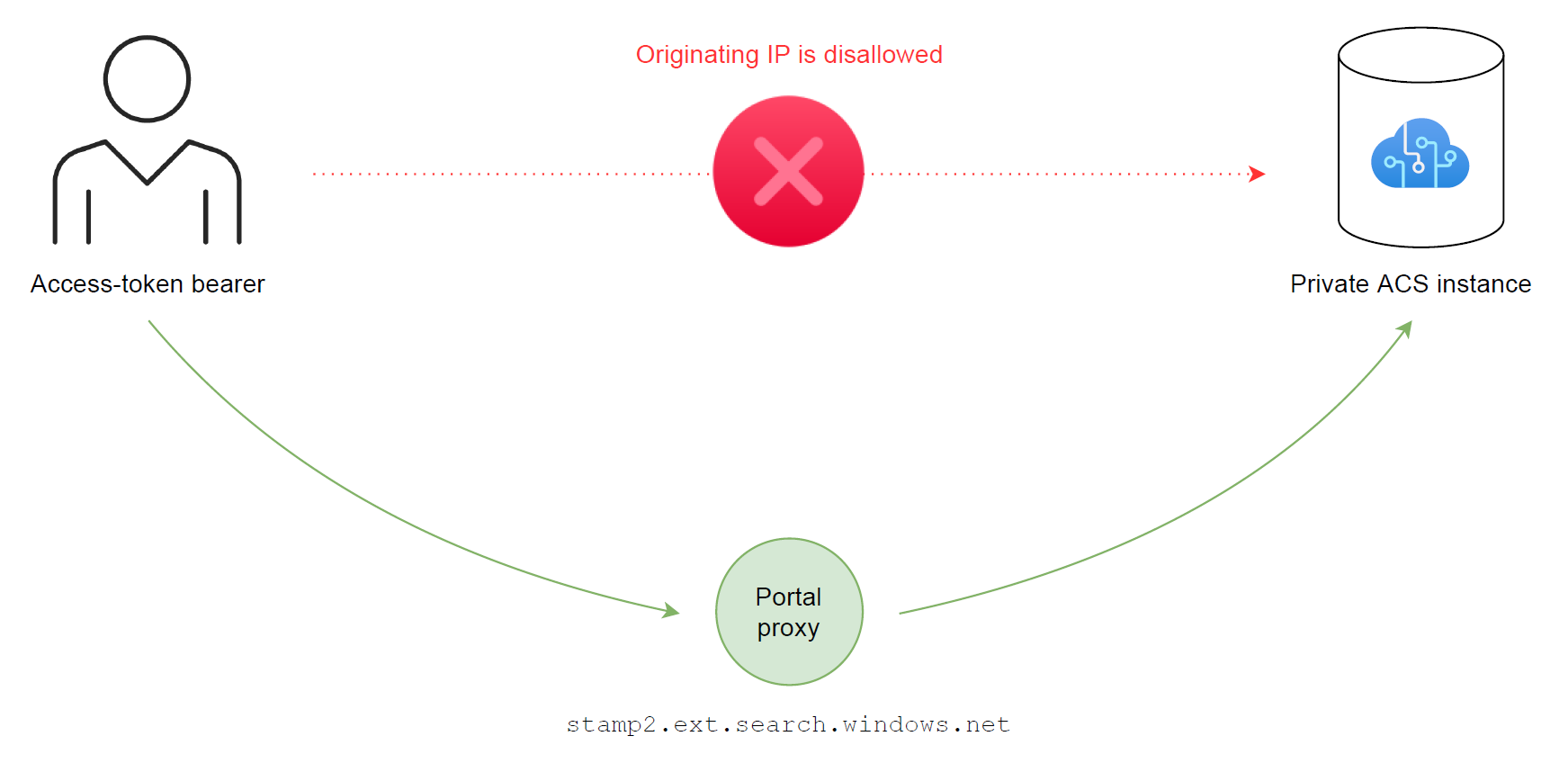

In other words, it seemed like the stamp2.ext.search.windows.net host was used as a whitelisted proxy, allowed to submit search queries on behalf of the bearer of the submitted access token.

At first, the use of the portal proxy (i.e. stamp2.ext.search.windows.net) seemed like a convenient approach, as it allowed a large number of users from different locations to access the data plane of a private ACS instance, without the need to whitelist every single IP address in the instance’s firewall.

Additionally, it allowed switching the traditional network perimeter in the form of IP whitelisting, with an identity perimeter relying on access tokens issued and managed by Entra ID instead. Note that whether a network perimeter should be replaced by an identity perimeter in the first place is a questionable choice, but digging into that subject is outside the scope of this article.

I assumed the access token submitted to the portal proxy was used for the following purposes and pursued therefore my investigation into that direction, to verify whether that was the case:

- Ensure the token was issued within the same tenant as the ACS instance

- Ensure the token was issued for a security principal with enough read permissions on the data plane of the queried ACS

To my surprise, it turned out that the only thing Microsoft was validating in the backend was that the submitted access token was still valid (i.e. not expired) and that it was issued for the https://management.core.windows.net/ audience, which corresponds to the Azure Resource Manager (ARM) API.

This effectively meant that given enough information, anybody could reach the data plane of my network-isolated ACS instance from any tenant and location, as obtaining a valid access token for the ARM API is as simple as logging into the Azure portal of any arbitrary tenant.

This seemed to answer my original question on whether the new feature made an exception for my instance of the Azure portal or if it made an exception for everybody. However, allowing anybody with enough information to reach the data plane of any ACS instance with the “Allow access from Portal” feature enabled, including those without any apparent network exposure (i.e. without a private, service or public endpoint), seemed more like a vulnerability to me than an intended purpose. I decided therefore to create a proof of concept and report the issue to Microsoft on February 23rd 2022.

Proof of Concept

The prerequisite to exploit this issue successfully was to gather enough information about a targeted ACS instance with the vulnerable feature enabled. The full set of information required was as follows:

- The name of the targeted instance

- The ID of the subscription where it was located

- The name of the resource group where it was located

- A valid API key to access its data plane (admin or query key)

- The name of the index to query

- A valid access token issued for the

https://management.core.windows.net/audience (can be acquired from any tenant) From there, retrieving data from the targeted instance using the whitelisted portal proxy was as simple as a single request. I made a curl template for Microsoft to reproduce the issue, where the information above could be filled in quickly and easily:

curl 'https://stamp2.ext.search.windows.net/api/subscriptions/<SUBSCRIPTION_ID>/resourceGroups/<RG_NAME>/providers/Microsoft.Search/searchServices/<SEARCH_SERVICE_NAME>/invoke' \

-H 'Authorization: Bearer <ACCESS_TOKEN>' \

-H 'x-ms-operation-name: Search.Invoke' \

-H 'x-ms-path-query: https://<SEARCH_SERVICE_NAME>.search.windows.net/indexes/<INDEX_NAME>/docs?api-version=2021-04-30-Preview&search=*' \

-H 'api-key: <API_KEY>' \

--compressed

As illustrated below with a simple proof of concept, retrieving data from my private ACS using an access token belonging to another tenant was fully possible:

Impact and disclosure

The ACSESSED vulnerability impacted all ACS instances deployed with the “Allow access from Portal” feature enabled.

By enabling that feature, customers effectively allowed cross-tenant access to the data plane of their ACS instances from any location, regardless of the actual network configurations of the latter. Note that this included instances exposed exclusively on private endpoints, as well as instances without any explicit network exposure, such as the one I deployed for investigation (i.e. instances without any private, service or public endpoint).

By the simple click of a button, customers were therefore able to turn on a vulnerable feature, which removed the entire network perimeter configured around their ACS instances, without providing any real identity perimeter (i.e. anybody could generate a valid access token for ARM).

I first reported the ACSESSED vulnerability on February 23rd as a privilege escalation with a moderate impact, according to Microsoft’s Security Update Severity Rating System. The issue was confirmed on March 22nd and its severity was raised from moderate to important, due to its cross-tenant aspect and easy exploitation.

Altogether, Microsoft used approximately 6 months to patch the issue from the day I reported the vulnerability on the Microsoft Security Response Center (MSCR) Researcher Portal. Since the ACSESSED vulnerability was only server-side and did not require Azure customers to take any specific actions, it did not get a CVE, as per Microsoft’s internal policy.

Disclosure timeline

- February 15th, 2022 – Discovery of the issue

- February 23rd, 2022 – Issue reported to Microsoft

- February 25th, 2022 – Report received by Microsoft

- March 22nd, 2022 – Confirmation of the issue and $10 000 USD bounty awarded by Microsoft

- March 25th, 2022 – Fix estimated by Microsoft to be deployed within the first week of May

- May 19th, 2022 – No fix, Microsoft reports working on a patch without specific technical details or ETA

- June 23rd 2022 – Microsoft reports that the fix requires “a significant design level change”

- August 31st, 2022 – Microsoft confirms that a fix has been applied to the vulnerable service

- September 12th, 2022 – Investigation of the new patch and confirmation of the bug fix

- October 2022 – Acknowledgement published on Microsoft’s MSRC acknowledgement page for online services (release date of the acknowledgement: August 31st, 2022)

Investigating the patch

Once Microsoft notified me on August 31st that a patch had been pushed to the ACS service, I decided to investigate it and re-test the ACSESSED vulnerability. I should mention that this part of the blog post is something I often miss from articles describing new vulnerabilities, as understanding how the issue was fixed is always interesting from a security point of view.

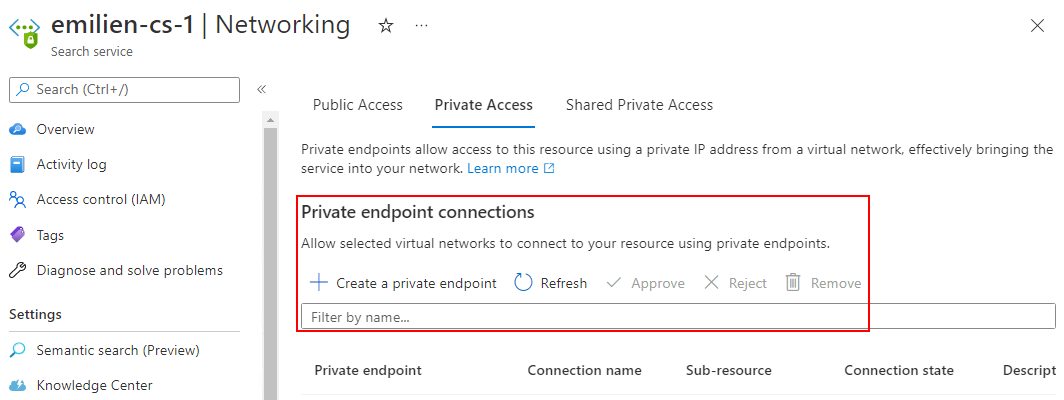

In order to investigate the patch, I followed the same procedure as the original investigation, by deploying a brand new instance of ACS in a test environment, using all the default options and disabling all network access completely.

I quickly noticed that the old button had now been replaced with a link to Microsoft’s documentation, explaining that allowing search queries through the Azure portal could be achieved by exposing the ACS on either a private or restricted public endpoint:

The first solution was to expose the ACS on a private endpoint and deploy a Virtual Machine (VM) with a web browser in the same Virtual Network (VNet) as the endpoint, while the second solution consisted of exposing the ACS on a public endpoint and whitelist the originating IP address of the user’s client. Note that the documentation still states that “allowing access from the portal IP address and your client IP address” is necessary for the second option, although whitelisting the client’s IP address seemed to be enough during the re-test.

My first observation was that the new design was significantly less complex than the previous one, as it essentially relied on IP whitelisting instead of using the portal proxy and all its complexity. Additionally, accessing the data plane of an ACS without any explicit network exposure was not possible anymore, which definitely removed some logical confusions about the feature. I originally expected Microsoft to stick with the original design and implement proper validation when submitting the access token to the portal proxy, to verify that it was issued for the same tenant as a queried ACS, and ensure that it was associated with a security principal with enough read permissions on the data plane of the ACS instance.

As shown above in the disclosure timeline however, Microsoft reported in June 2022 that the patch required “a significant design-level change”, which ultimately resulted in a simplified design. One disadvantage of that new design is that each person who needs to query an ACS through the Azure portal needs to whitelist their IP address in the instance’s firewall, which might be a pain in situations where a large number of users need to interact with the data plane of an ACS.

This might actually be the initial reason for the original design, where based on my understanding, the idea was to whitelist a single service tag (i.e. AzurePortal) and rely on identities to provide access to the data plane of an ACS instance, therefore avoiding the need for whitelisting multiple IP addresses. Even if patched correctly, the main drawback of that design was the lack of clarity, as “Allow access from portal” was clearly a networking feature, but the list of principals with the ability to bypass network restrictions via the portal proxy was found in the Identity and Access Management (IAM) section of the ACS’ configuration.

The current design provides therefore more transparency and clarity, as anyone who is able to access the data plane of an ACS is now required to whitelist their IP address in the firewall of the instance, which makes it a lot easier to keep an overview of all the entities allowed to query an ACS, compared to the previous implementation.

Finally, I wanted to verify if it was still possible to exclude the AzurePortal service tag from the network configurations of my new ACS instance, and see if I could still query its data plane through the portal proxy.

Since the “Allow access from Portal” button was gone, I investigated the Cognitive Search API to set the value of the bypass property in the ACS instance to AzurePortal manually. To my surprise, this was still possible (probably to avoid breaking changes in the resource’s data model). However, querying the data plane of the new ACS instance via the portal proxy did not work anymore, as trying to use the invoke method from the original design returned the following response, suggesting that the function was now disabled by Microsoft:

{"error":{"code":"","message":"Invoke URI requests are disabled"}}

Potential areas of further research

In the end, it remained unclear whether the ACSESSED vulnerability impacted other Azure services, as several resources have a similar feature, but it is not always implemented in the same way. For example, Azure Cosmos DB has a networking feature called “Allow access from Azure Portal”, which once enabled, whitelists specific IP addresses in the resource’s firewall, instead of relying on the portal proxy. Network-bypass functionalities constitute therefore an interesting area of research, as such features can potentially open the doors for more bypasses than what is intended in the first place.

Concluding remarks

The ACSESSED vulnerability is a very good example of how enabling a simple feature can significantly deteriorate the security posture of an environment without even realising it.

Hopefully, this blog post will help raising awareness about the importance of being critical to cloud features and services, as well as technology in general, even when developed by well-established vendors such as Microsoft.

Although the use of a specific cloud technology implies having a certain level of trust towards its provider, issues like the ACSESSED vulnerability highlight the importance of gaining a deeper understanding of cloud services than what may be acquired through documentation only. I hope this article will help inspire cloud professionals to explore even the simplest feature introduced in their favourite services, and be critical to the security implications of those additions.