Managing vulnerabilities in software containers: how to avoid common pitfalls

TL;DR

This blog post provides a technical description of the most common pitfalls when using static scanners to discover vulnerabilities in container images.

Although used in a vast majority of deployment pipelines, the inner workings of these scanners are often misunderstood by dev teams. This leads to an inappropriate use of the technology, which in turn leaves the user with a false sense of security.

The goal of this article is to raise awareness about the actual capabilities of those scanners and help dev teams understand what they can and cannot do. Organisations developing containerized applications should review how they use static vulnerability scanners for container images in their pipeline, to ensure they are using that technology correctly.

This blog post covers the following:

- A high-level description of the main approaches used by most static scanners to find vulnerabilities in container images

- A critical view on the approaches used by those scanners and the most common pitfalls to avoid

- The challenges that come along with patching vulnerabilities in container images

- Recommendations on how to manage vulnerabilities in software containers securely

Introduction

Over the past few years, the use of software containers in enterprise environments has become extremely popular due to the industry shift from traditional silo deployments to micro-service architectures. Deployment pipelines are slowly incorporating more and more automated security tools to help shifting left and catch vulnerabilities as early as possible during the development process. One of the most common tools found in those pipelines are what most people refer to as “container scanners.”

A “container scanner” is a very broad term, which really does not say anything about the scanner’s approach for analysis or the type of issues it tries to detect. On one hand, a container scanner may be either static or dynamic, and can focus on analysing the running container itself, or its static image (sometimes both). On the other hand, a container scanner may search for a very specific type of issue or multiple ones at the same time, such as software vulnerabilities, malware or deviations from recommended security best practices.

Nonetheless, when developers talk about “container scanning”, they most of the time refer to a static scanner analysing Linux-based container images for software vulnerabilities. We will see that such scanners tend to use a rather simple approach to discover vulnerabilities, which can give dev teams a false sense of security when misunderstood and/or used inappropriately in their pipelines.

Note that this article does not mention any container-scanning product or vendor on purpose, as the goal of this blog post is to explain the general approach and pitfalls of most static scanners to find vulnerabilities in container images, rather than pointing fingers at specific vendors.

Background

Before jumping into the inner workings of static vulnerability scanners for container images, we first need to understand what container images actually are. Container images consist of the central piece of software containerisation, as they are the ones software containers are built upon.

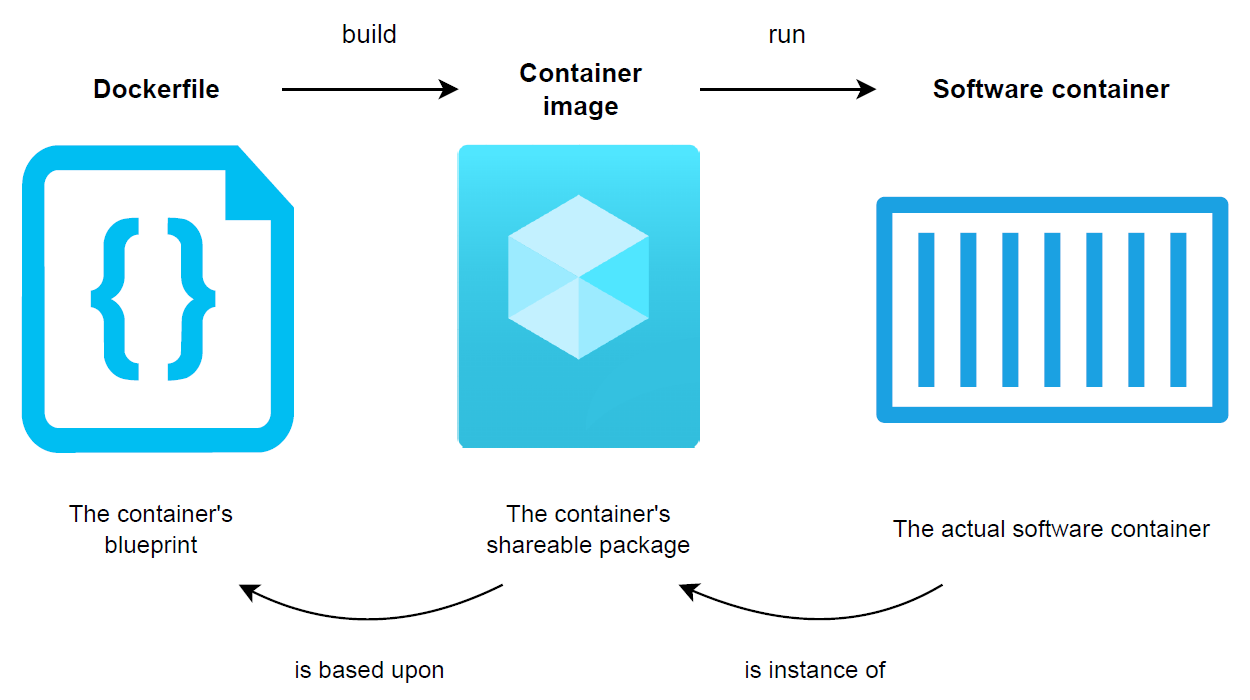

As illustrated below, the process for creating a software container starts with a simple text file called a Dockerfile (on the left). The latter is often referred to as the container’s blueprint, as it holds the instructions describing what the end container will look like in terms of directories, as well as software packages it will contain. A Dockerfile is then built into an immutable container image (in the middle), which represents the container’s shareable package that can be used to “ship code”. A software container (on the right) only consists of an instantiation of a container image. Container images are therefore the central piece of the containerisation process, as they consist of the actual packages that can be shared with others.

Figure 1: The creation process of a software container

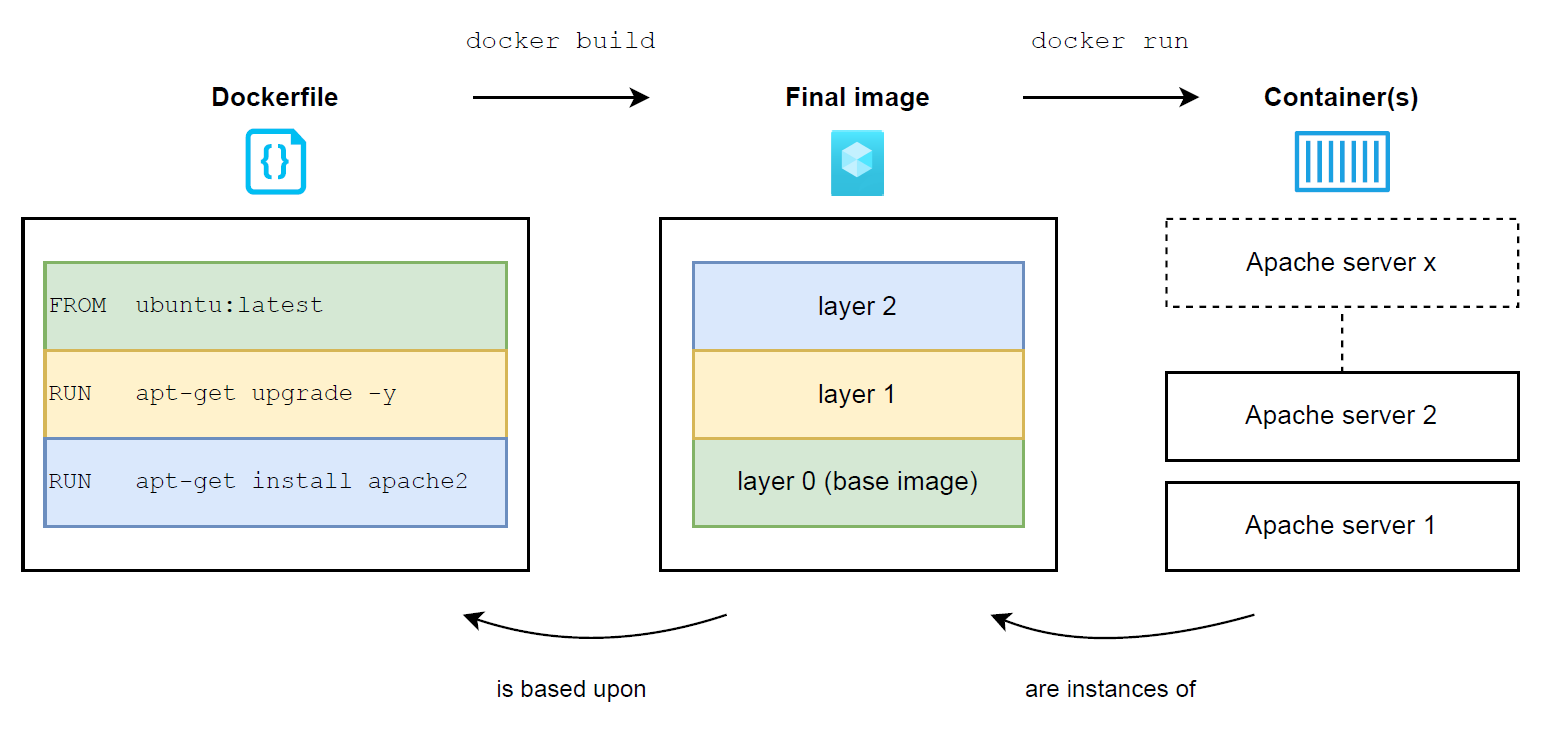

It is important to understand that container images are actually made out of layers, where each layer corresponds to an instruction defined in the image’s Dockerfile. Thanks to this layering system, container images are able to build upon each other, in order to avoid building everything from scratch every single time. As illustrated below, the high-level process for building a container image based on another one is as follows:

- The container-runtime manager (typically containerd or CRI-O) downloads the image specified in the FROM instruction from its corresponding registry, in order to be used as a base image referred to as “layer 0” (since no explicit registry is defined, Docker Hub is used implicitly in this case)

- The base image is extended with upgraded packages and results in a new intermediate image composed of 2 layers (layer 0 and 1)

- The “layer 1 image” is extended with a new package and results in a second intermediate image composed of 3 layers (layer 0, layer 1 and layer 2)

- Since there is no more instruction in the Dockerfile, the second image containing all the layers is what becomes referred to as the “final image“. The final image is the output expected by the end user and corresponds to the image built out of the provided Dockerfile at the beginning of the process

- At this point, the final image can be instantiated into one or multiple containers

Figure 2: Visualisation of the layering system, showing how to build a container image based on another one

How do most static scanners detect vulnerabilities in container images?

The high-level approach used by most static scanners to find vulnerabilities in a container image consists of 2 main steps:

- Identify all the packages present in the image with their associated versions

- Search for known vulnerabilities in each of the discovered packages

The first step here is crucial, as the scanner’s ability to find vulnerabilities is only as good as its ability to discover all packages within an image in the first place.

Packages are divided in two categories, depending on their nature. On one hand, system packages consist of the binaries used by the Linux distribution included in the image (e.g. busybox, glibc, openssl, etc.), and are usually installed via a package manager such as apk, yum or apt, depending on the distribution. On the other hand, application packages consist of dependency libraries required by a containerised application to function properly and are usually installed via an application-specific package manager. For example, common application packages for a Python application are datetime, importlib or requests, and are usually installed through pip, the Package Installer for Python.

Once a scanner has indexed all system and application packages in an image with their respective versions, the next step is to go through each package and verify whether a known vulnerability has been disclosed for it. An appropriate database is typically used for each type of package, depending on their nature. For example, the National Vulnerability Database (NVD), the Red Hat Security Advisory database (RHSA) or the Debian Security Bug Tracker are typical sources used by static scanners to identify disclosed vulnerabilities in a system package. Similarly, appropriate data sources such as Safety DB for Python or the Node.js Working Group’s vulnerability database are commonly used by open-source scanners to detect vulnerabilities in application packages.

Note that not all static vulnerability scanners for container images support the detection of application packages. Furthermore, scanners that support that feature usually support a limited set of programming languages.

Finally, note that open-source scanners tend to use multiple open-source vulnerability databases to detect known vulnerabilities (especially for application packages), whereas commercial products may sometimes use their own closed-source database which indexes multiple sources upstream.

Pitfalls of the approach adopted by most static vulnerability scanners for container images

As explained above, the high-level approach used by most static scanners to find vulnerabilities in container images is rather simple and comes with a certain number of pitfalls, making the detection of specific vulnerabilities challenging.

Pitfall 1: Vulnerabilities in system packages installed outside of a package manager are usually not detected

Many static scanners rely on the presence of a package manager in a container image to detect system packages in the first place. The approach usually consists of parsing the database file associated with the package manager present in the image, as it contains a list of all installed packages with their associated versions. The actual database file that is parsed during that process varies from one package manager to another, and is largely dependent on the underlying Linux distribution used as a base for the container image.

Typically, most static vulnerability scanners parse one of the following files to detect system packages in a container image (non-exhaustive list):

| Package manager | Parsed database file |

|---|---|

| apk | /lib/apk/db/installed |

| apt apt-get dpkg |

/var/lib/dpkg/status |

| yum rpm |

/var/lib/rpm/Packages |

Thus, in case a system package is installed outside a package manager during the container-image building process (e.g. installed from source), that package will not be indexed in one of the above files and will not be detected as such by the static scanner. Since the package cannot be detected, the potential vulnerabilities it may contain will not be discovered either.

Dev teams installing packages from source in container images should therefore be aware that most static vulnerability scanners will not be able to find vulnerabilities in such binaries.

Pitfall 2: Vulnerabilities in custom system packages are usually not detected

Sometimes, dev teams might be extending an already-existing system package, in order to include custom functions (sometimes referred to as “self-compiled packages”), therefore updating the package’s version and sometimes even its name to a custom one.

As explained previously, the core structure of most static vulnerability scanners for container images relies heavily on external vulnerability databases, which only contain information for official packages and versions. Thus, although a custom system package is detected correctly by a static scanner (e.g. by installing it via a package manager), the package will never be detected as vulnerable (although it may actually be), as no vulnerability database will contain a match for that particular package name and version combination.

Note that this particular issue is more related to the way vulnerability detection works (i.e. relying solely on the use of vulnerability databases for official packages), rather than an issue specifically related to static vulnerability scanners for container images.

Nonetheless, dev teams customising system packages during the container-image building process with a different name and/or version than what is official, should make sure they are not relying on static image scanners to find vulnerabilities in such binaries, as most of scanners will not be able to detect them.

Pitfall 3: Vulnerabilities in application packages are not always detected

As explained previously, application packages consist of dependency libraries required by a containerised application to function properly.

The detection of vulnerabilities in application packages is very scanner-dependent, as not all scanners are able to detect such packages in the first place. For those that support that feature, the approach is similar to the one used to detect system packages, as it consists of parsing a specific file listing out the dependencies required by a main application. The actual dependency file that is parsed during that process varies depending on the language and framework of the main containerised application requiring the dependencies.

Typically, most static vulnerability scanners supporting the detection of application packages parse one of the following files to detect such dependencies in a container image (non-exhaustive list):

| Application language | Parsed dependency file |

|---|---|

| C# | project.json *.csproj *.fsproj |

| F# | project.json *.fsproj |

| Go | go.mod Gopkg.lock vendor.json |

| Java | build.gradle build.gradle.kts build.sbt pom.xml |

| Node.js | package.json package-lock.json yarn.lock |

| PHP | composer.lock |

| Python | Pipfile.lock poetry.lock requirements.txt |

| Ruby | Gemfile.lock |

| Rust | Cargo.lock |

| Visual Basic | project.json *.vbproj |

| Misc | *.sln obj.assets.json project.assets.json packages.config |

Most dev teams build container images with applications requiring dependencies. I cannot remember the number of pipelines I have seen with a static vulnerability scanner that either did not support the detection of application packages altogether, or did not support the programming language used by the developers.

Dev teams should therefore review whether the scanner they are currently using is capable of detecting application packages for the type of application(s) they are developing, as vulnerabilities in such packages might go under the radar if that is not the case. Additionally, dev teams should make sure they understand how the static scanner detects the dependency file for their application, as some scanners are only able to detect such files in the working directory of an application, while others are able to detect it regardless of its location on the file system.

Pitfall 4: Vulnerabilities in discovered packages are not always detected

As discussed so far, the first challenge for a static vulnerability scanner is to detect all system and application packages within a container image, as a scanner’s ability to find vulnerabilities is only as good as its ability to discover all packages within a container image in the first place.

Assuming that all packages are discovered and indexed properly, the second challenge for such scanners is to make sure all known vulnerabilities within each package are identified correctly, which implies using appropriate data sources for each type of package discovered within an image (i.e. system or application). Thus, a scanner’s ability to find vulnerabilities also depends largely on the type of vulnerability databases it uses, as well as the quality of its algorithm to parse from different sources.

Sometimes, certain scanners tend to use obscure data sources with questionable completeness and maintenance. For example, many scanners use or have used the Alpine SecDB, which based on its description, consists of a vulnerability database for system packages in Alpine Linux with “backported fixes”. The last part of the official description is actually crucial, as it means that any package in Alpine Linux known to be vulnerable, but without a fix, or with a patch that has not been backported to older versions of the package, is not contained in the Alpine SecDB. I have seen multiple pipelines where dev teams were scanning custom Alpine-based images with a scanner using that database as its only source of CVEs for the distribution. In some cases, almost half of the vulnerabilities actually present in the system packages of their images were left undetected, compared to other scanners with more complete databases.

The effective data sources used for detecting vulnerabilities in both system and application packages of different kinds (i.e. multiple Linux distributions and application languages) are therefore crucial to provide a good coverage of the vulnerabilities present in a container image. Note that open-source scanners tend to use multiple open-source databases to detect known vulnerabilities (especially for application packages), whereas commercial products typically use their own closed-source database which indexes multiple sources upstream.

Dev teams relying on a static scanner to find vulnerabilities in container images should therefore ensure they understand the origin of the databases their scanner uses, as well as the eventual weaknesses that come along with these data sources (i.e. types of vulnerabilities that may be missing). A common issue with many data sources indexing disclosed vulnerabilities is that they only contain vulnerabilities with an existing patch, therefore missing all known but unpatched vulnerabilities (this is partly the case with the Alpine SecDB). Additionally, reviewing the maintainer(s) and update frequency might be a good indicator of the reliability of a vulnerability database.

Note that conducting that kind of verification is usually easy with open-source scanners, as you can always have a look at their source code in case they do not document properly the vulnerability databases they use as data sources. Regarding closed-source scanners, some of them may disclose what kind of databases they use, while others might not. Trusting that the company behind a closed-source scanner is using trustworthy and complete vulnerability databases is however a part of the implied trust when using a remunerated service of this kind. Nonetheless, dev teams may always ask them to share internal documentation to prove the completeness of their vulnerability databases if possible.

What about patching vulnerabilities once they are discovered?

The next step of the vulnerability-management process is to triage the vulnerabilities reported by a static scanner to prioritise security patching.

For some reason, a lot of companies tend to build container images based on a full Linux distribution such as Debian, Ubuntu, Red Hat or Alpine Linux. Dev teams using that approach probably know that scanning images usually end up with hundreds, if not thousands of reported vulnerabilities, depending on the number of images to scan. Due to that massive number, a lot of companies tend to triage only vulnerabilities with an estimated high or critical impact, while ignoring the rest.

Triaging is an expensive activity, as it ultimately requires a human to analyse and determine whether each reported vulnerability should be patched. Based on my experience, many companies tend to get around that challenge, by requiring all critical and high vulnerabilities to be patched as fast as possible, regardless of their actual exploitability in a containerised context.

Nonetheless, patching vulnerabilities in container images is not always as straightforward as it may seem and can rapidly become a nightmare when many of them are inherited. As previously explained in the background section of this article, container images are made out of layers, where each layer corresponds to an instruction defined in the image’s original Dockerfile. Thanks to this layering system, container images are able to build upon each other, in order to avoid building everything from scratch all the time.

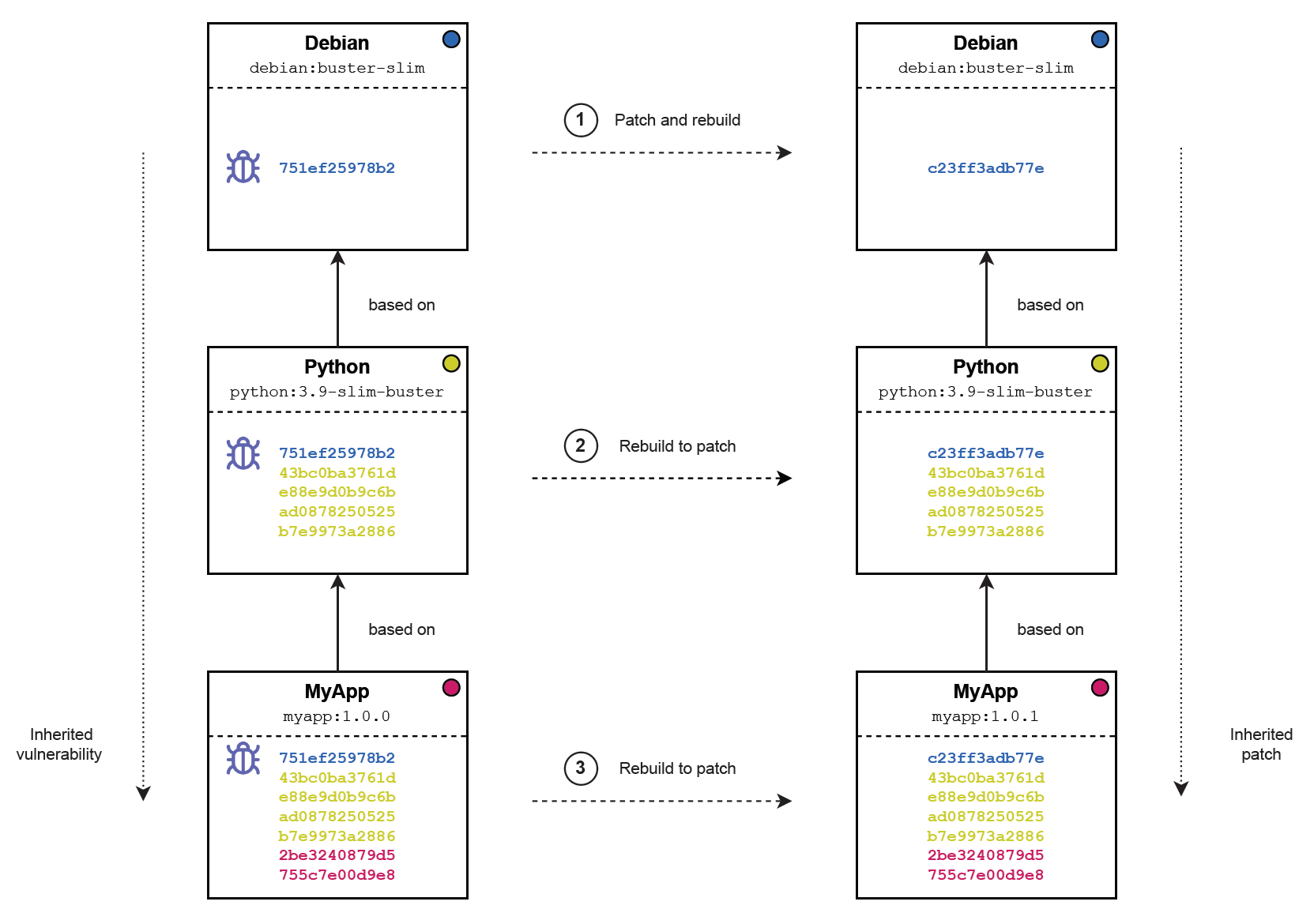

However, patching an image with a vulnerability originating from a parent can be hard to manage if the parent image in question is not controlled by the dev team or the latter’s organisation. Even worse, there are situations where a custom-made image contains a vulnerability that needs to be patched, but originates from its grandparent image or even its great grandparent, requiring multiple images to be patched upstream, which may sometimes be managed by different companies. As illustrated below, a scenario of this kind requires the following in order for a company to ultimately patch a vulnerability inherited by a grandparent image:

- The developers of the grandparent image where the vulnerability originates need to rebuild the image with a patch (debian:buster-slim in this case)

- Only once the grandparent is rebuilt, the developers of the parent image (python:3.9-slim-buster in this case) can rebuild it to inherit the new patched layers from the grandparent

- Only once the parent is rebuilt, the company can finally patch its custom image (myapp:1.0.0 in this case), by rebuilding it and inherit the patched layers from its parent Note that every child image needs to wait for their parent to rebuild and inherit patched layers from their own parent before they can re-build themselves. In case a vulnerability is originating from a grandparent or higher, any child that fails to rebuild may prevent the rest of the chain to inherit the patch.

Figure 3: Workflow required to patch a vulnerability inherited by a grandparent images

As we can see, patching vulnerabilities in container images can rapidly become a nightmare when many parent images are involved and many vulnerabilities need to be patched. If the parent images are controlled by other entities, the complexity of vulnerability patching increases even more, as it introduces external dependencies upstream.

Due to that complexity, I have seen companies that had given up completely on patching vulnerabilities in their container images, while others have tried to minimise the number of upstream dependencies, by building all their images on a single Linux distribution with no other parent (typically Alpine Linux).

How to manage vulnerabilities in software containers securely

The easiest solution to manage vulnerabilities in software containers is to avoid having a large number of packages present in your images, hence removing the presence of potential vulnerabilities by going distroless.

As briefly mentioned in the previous section, most companies tend to build container images based on a full Linux distribution such as Debian, Ubuntu, Red Hat Linux or Alpine. Such images contain a large number of system packages that are most of the time completely unnecessary for running a containerised application, but provide threat actors a full set of tools to play with if they get access to the container once it is running. Personally, I am a strong advocate of distroless images as they almost remove the entire attack surface introduced by system packages, which are not even necessary in the first place.

Distroless images are container images that only contain the developer’s application and its required dependencies, as well as the runtime environment necessary to run it (e.g. a Python interpreter for a Python application, a Java Virtual Machine for a Java application, etc.). Due to their extreme simplicity, distroless images remove therefore the necessity and pain of dealing with vulnerabilities in system packages, while allowing dev teams to shift left and focus on securing their source code instead.

Since almost no system package is present in a distroless image apart from the application’s runtime environment, the need for vulnerability scanning is minimal and suddenly easy to handle. Application dependencies can still be scanned for vulnerabilities at this stage of the pipeline, or directly in source code before being built into a container image to shift left even more. No matter the approach, the use of distroless images provides companies a way to minimise the necessity for vulnerability management in container images, while avoiding a lot of headaches.

My experience after assisting many organisations on this subject matter is that distroless images are still largely unknown, despite Google’s push to popularise them. In almost all cases, container images based on full Linux distributions (sometimes referred to as distrofull) can be replaced with distroless alternatives, without even changing the dev team’s workflow once the changes are implemented. The only exception might be if the team already uses a deployment pipeline that is part of some kind of framework, which generates distrofull images without the possibility to modify that aspect easily. In that case, modifying the framework’s built-in pipeline is always a possibility, but usually requires an investment that not all companies are willing to make.

Concluding remarks

Despite the growing popularity and excitement around the technology, software containers are still a misunderstood beast in many ways. Developers always seem so surprised when mentioning the existence of distroless images, or pointing out some of the pitfalls that come along with “container scanners”.

Hopefully, this blog post will help raising awareness about those pitfalls, while providing a better understanding of the inner working and actual capabilities of most static vulnerability scanners for container images.

Based on previous experience, approaches combining the use of distroless images and a well-understood image scanner have proven to be efficient strategies for managing vulnerabilities in container images. I hope this contribution will help companies understand the importance of an appropriate use of static vulnerability scanners for container images, and avoid common pitfalls that too often provide a false sense of security in deployment pipelines.